Design Circular Workspaces: One Room at a Time

Henri Alain Chazelles

CPD Provider-Events and Workshops for the Architecture, Design, and Building Industry

November 13, 2025

Featured Author: Alan Boyd

Published by: InHouseGroup3

It was a warm Sydney evening, 27 February 2008. I had a mission, to pick up “the German Professor”, flying in directly from Europe. Tall, slender with long dark hair over his collar, dressed, unseasonably for Australia, head-to-toe in black with a leather jacket– at first glance, he could’ve been the bassist from a German goth rock band.

He wasn’t.

He was Professor Dr Michael Braungart, one of the world’s leading environmental chemists and co-creator of the “cradle-to-cradle” framework with the architect Bill McDonough. I’d invited him to Sydney to speak at the Green Building Council of Australia’s Sustainable Cities Conference, sponsored by the company I worked for at the time, Herman Miller.

As he threw his bag into the back of the car, he turned to me and asked:

“Alan, am I restricted in anything I say when I’m at the conference?”

Being me, I said: “Go for your life, mate. Nothing’s off the table.”

The next day, in front of about 1,000 people, he stepped up to the lectern and opened with:

“I vowed, after visiting Australia once, that I would never come back. Because how could such a large country, in such a short time, be destroyed by so few people?”

You could almost hear the jaws hitting the floor. Then he looked over at me and said:

“This conference is entitled ‘Sustainable Cities’. Alan, if I asked you what your relationship with your wife is like, and you said ‘sustainable’, I think we have a problem. I don’t believe in sustainability. There must be more to life than just sustainability.”

He went on to describe the concept of his book co-authored with McDonough “Cradle to Cradle - Remaking the Way We Make Things” – that idea has been lodged in my brain ever since. Almost two decades on, Australia now has a national circular economy engineering strategy on the table: Engineering for Australia’s Circular Economy: A National Strategy, launched by Circular Australia and Engineers Australia. It’s deliberately framed as a toolkit to move us beyond “being less bad” and into redesigning our systems – including how we plan, design and build workplaces. So, you are looking at all of this – circular economy, waste targets, embodied carbon, ESG – and asking: “Okay, but what does this actually mean for the way we design offices?” Meeting rooms are good examples of how you can increase circularity. We need to stop designing meeting rooms as if they’re permanent, when we know now more than ever, that they’re not. From “less bad” to genuinely circular. For years, much of our work in the built environment has sat under the banner of sustainability:

He went on to describe the concept of his book co-authored with McDonough “Cradle to Cradle - Remaking the Way We Make Things” – that idea has been lodged in my brain ever since. Almost two decades on, Australia now has a national circular economy engineering strategy on the table: Engineering for Australia’s Circular Economy: A National Strategy, launched by Circular Australia and Engineers Australia. It’s deliberately framed as a toolkit to move us beyond “being less bad” and into redesigning our systems – including how we plan, design and build workplaces. So, you are looking at all of this – circular economy, waste targets, embodied carbon, ESG – and asking: “Okay, but what does this actually mean for the way we design offices?” Meeting rooms are good examples of how you can increase circularity. We need to stop designing meeting rooms as if they’re permanent, when we know now more than ever, that they’re not. From “less bad” to genuinely circular. For years, much of our work in the built environment has sat under the banner of sustainability:

- Use a bit less energy.

- Specify some recycled content.

- Divert as much as we can from landfill at the end.

But that was for many, just ticking a few boxes and as “the Professor” was not so subtly hinting at in that Sydney lecture theatre, “sustainable” can sometimes just mean “a bitless damaging”.

This new circular strategy pushes us to ask different questions:

- Can this product, space or system be designed for multiple lives, not one?

- Can materials moves in loops - from build to rebuild to reuse and remanufacturing - rather than ending in a skip?

- Can we design for change and churn, instead of pretending it won't happen?

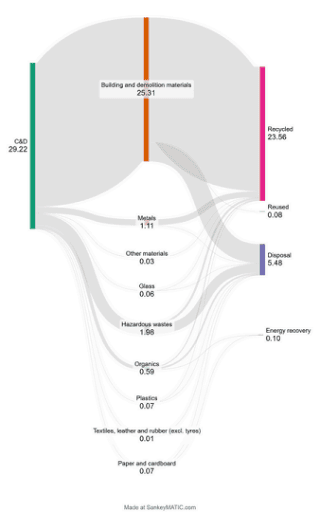

When you look at the numbers, you see why the focus has landed so firmly on the built environment. In 2022-23, Australia generated 75.6 millions tons of waste, and 29.8 million tons of that was from construction and demolition. I don't think that has gone down.

Australia's C&D waste flows 2022-23: 29.22 million tonnes in, with 23.56Mt recycled, 5.48Mt to landfill, & just 0.08Mt reused. Credit: Engineers Australia. The Sankey diagram shows Australia's Construction and Demolition (C&D) waste flows for 2022-23, with 29.22 million tonnes total C&D waste breaking down into various

material streams (building/demolition materials at 25.31Mt, metals at 1.11Mt, glass at0.06Mt, plastics at 0.07Mt, organics at 0.59Mt, etc.) and their fates (recycled 23.56Mt,reused 0.08Mt, disposal 5.48Mt, energy recovery 0.10Mt). Credit: Engineers Australia, A National Strategy for a Circular Economy.

material streams (building/demolition materials at 25.31Mt, metals at 1.11Mt, glass at0.06Mt, plastics at 0.07Mt, organics at 0.59Mt, etc.) and their fates (recycled 23.56Mt,reused 0.08Mt, disposal 5.48Mt, energy recovery 0.10Mt). Credit: Engineers Australia, A National Strategy for a Circular Economy.

The hidden cost of linear design: 29.8 million tonnes of construction waste in 2022-23,much of it avoidable. Credit: Stock image/AI-generated. The uncomfortable truth is that we are still thinking short-term, designing fit-outs as if demolition doesn’t matter. So, let’s use a meeting room as an example. Right now, we have linear rooms in a world that is moving to circularity.

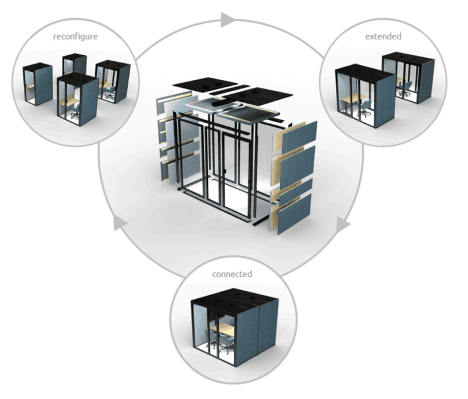

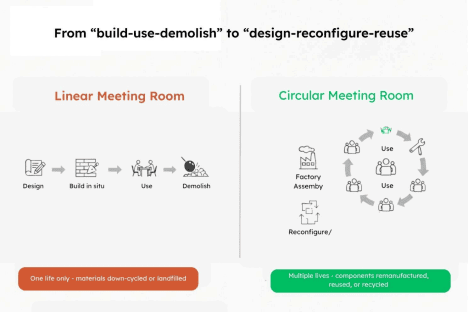

From linear to circular: A meeting room's lifecycle - single-use & demolition-bound vs multiple lives through reconfiguration & reuse.

Credit: Alan Boyd/AI.

Credit: Alan Boyd/AI.

If you look at a typical meeting room's life:

- Design - Draw a box consisting of plasterboard, services, glass, doors, bulkheads, and finishes.

- Construction - Built in situ. Wet trades. Mixed materials. Layers of board, insulation, paint, and adhesives.

- Use - It serves its purpose for a few years. Headcount changes. Leadership and strategy shift. Often, large rooms are under-utilised while other smaller meeting rooms are over-booked.

- End of life - The lease ends or perhaps a new workplace strategy arrives, or the floor is sub-leased. The room is demolished, and the materials end up in a landfill.

There are three obvious circular red flags in that pattern:

- Short life, high impactThe room might last the length of the lease, which is often getting shorter post-COVID. The embodied carbon and resources locked up in it will sit in the atmosphere and landfill for far longer.

- Make good, demolition, and repairStandard “back-to-base-building” make-good clauses often demand that rooms be demolished wholesale, even when the next tenant wants similar spaces. Extra financial and carbon cost.

- No design for disassemblyWet trades and complex junctions make separation and, therefore, high-value recovery almost impossible. The circular engineering strategy is very clear: if we’re serious about circularity, the way we design and plan fit-outs – especially enclosed spaces – is no longer defensible. The good news is that architects and designers are incredibly well placed to change this, because they control the early decisions that make circularity possible. They can create an ecosystem that makes change easy and increases flexibility for the client while reducing costs and carbon emissions.

The circular pillars - through a design lens

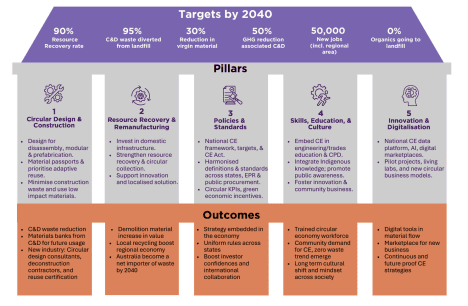

The Engineers Australia white paper organises its recommendations into five pillars. Rather that treat those as policy headings, it's useful to translate them into design questions for your next project.

The Engineers Australia white paper organises its recommendations into five pillars. Rather that treat those as policy headings, it's useful to translate them into design questions for your next project.

- Circular design and constructionIf you know it comes apart - and where the panels, doors, and glass go next - you're much closer to circular design than most projects currently get.Primary idea: design things so they can change, be taken apart, and be used again. Ask yourself: Can this room be disassembled without destroying its components? Are we using modular systems that can scale up, down or sideways? Are we getting the same performance (acoustic, privacy, fire) with fewer kilos of material? In practice, this means using modular systems or pods for high-churn rooms instead of stud-built plasterboard; employing dry fixings wherever possible – screws, clips, mechanical brackets – instead of hidden glues and wet trades; and designing parts that can be disassembled with basic tools.

The circular alternative: Modular pods designed for disassembly, relocation, & multiple lives. Same function on Day 1, different story on Day 2000. Credit: Ecolution Design (ecolutiondesign.eu) - Resource recovery and remanufacturing systemsPrimary idea: keep materials moving in useful loops at their highest possible value.

Design questions: Could this space, or components of it, be relocated and reassembled elsewhere on the floor or in another building? Is there a secondary market or take-back scheme for the systems we’re specifying? Are we labelling and documenting materials so that whoever comes after us knows what they can reuse?

Think about a simple enclosed focus room:- Built traditionally, it's demolished in 5-10 years, now maybe less.

- Designed as a modular room or pod, it's an asset that can move with the tenant. be sold. leased, refurbished or remanufactured.

Same function on Day 1, Completely different story on Day 2000. - Policy and StandardsPrimary idea: rules and incentives are shifting in favour of circular options.

We’re already seeing government clients talking about circular procurement and reuse targets; ratings tools looking at embodied carbon, waste and resource recovery plans more deeply; and stronger scrutiny from investors and ESG teams on strip-out waste and fit-out carbon. For architects and designers, that means anticipating these shifts in your specs and client advice, not scrambling to retrofit circular thinking at the end. It also means choosing interior systems – including rooms, pods and partitioning – that come with credible performance data, environmental product declarations (EPDs) and clear end-of-life pathways, not just a “recyclable” icon in the brochure. - Culture, skills, and capacityPrimary idea: people need to see and participate in circularity.

Are you having the “what happens in 3, 5,10 years?” conversation with clients in the briefing phase? Are modular rooms and pods positioned as core workplace tools – not just add-ons? Are you creating spaces where staff can literally see circularity happen –rooms being shifted, recombined and reused, not just demolished? A single visible move – say, turning two 2-person rooms into one 4-person room by reconfiguring panels rather than calling in demolition – can do more to explain circularity to staff than a hundred sustainability posters. - Innovation and digital toolsPrimary idea: data makes circularity practical.

Are you using BIM and digital models to tag systems and materials with useful circular information (recycled content, disassembly method, expected lifespan)? Are you choosing manufacturers who are ready to provide product-level environmental data such as third party EPD’s? Are you handing over a clear, structured record of what can be moved, reused or refurbished when the fit-out eventually changes?

This is where modular rooms and pods can punch above their weight: each one can carry a simple data set – materials, carbon, moves, upgrades – that become feeds into the client’s wider ESG and asset strategy.

Meeting rooms and pods as a circular example.

A common brief might sound like this:

“We need a mix of 2–4-person meeting rooms, some larger project spaces, a few focus rooms and some individual phone booths or pods. ”The default response is still, in many projects, a few phone booths and a run of plasterboard and glass boxes of different sizes, detailed beautifully and built once. A circular response starts with a different question. “What’s the simplest kit of parts that can deliver these functions now and be reconfigured or relocated as the organisation changes? ”That’s where modular rooms and pods come into their own. Not as a gimmick, but as a deliberate circular strategy for high-churn zones.

Handled well, they allow you to:

- Align with circular design and construction - factory-built modules designed for assembly, disassembly and reconfiguration, including floorless options that sit on existing finishes.

- Support resource recovery and remanufacturing - rooms that can be picked up and moved, and components that can be refurbished, reskinned or remanufactured rather than scrapped.

- Make compliance and policy easier, not harder - repeatable performance data (acoustics, airflow, lighting, power) that helps satisfy code, ratings tools and future circular procurement rules.

- Shift culture and capability - facilities teams who become used to reconfiguring rather than demolishing, and staff who see the workplace evolve without skips full of rubbish.

- Embed digital traceability from day one - each module or room tagged in BIM and asset systems with location, configuration and lifecycle information.

The key point here is not that all rooms must be modular. It's that you match the ecosystem to the churn:

- Use more permanent construction for truly stable elements (large boardrooms, long-term lab or clinical spaces).

- Use modular movable re-locatable systems for the rooms you know will be or could be moved as the business changes.

That's exactly where circularity and good workplace design naturally intersect.

Practical moves for your next project.

You don't have to wait for a "Circular Economy Act" or a mandatory standard to start applying this thinking. On your very next project, you could:

You don't have to wait for a "Circular Economy Act" or a mandatory standard to start applying this thinking. On your very next project, you could:

- Change the conversationAsk clients how often they’ve reconfigured meeting spaces or how often they wanted to and couldn’t or moved in the last decade. Put churn and “move scenarios” of the Day 1plan. A workplace should be able to adapt, modularity and circularity allows flexibility. Look to frame circularity as risk management (waste costs, make-good exposure, stranded assets), not just an ethical “nice to have”, and as a reduction in total cost of ownership.

- Design for disassembly in the detailsChoose systems that can be taken apart cleanly. Keep build-ups simple: fewer layers, fewer incompatible materials glued together. Make a habit of documenting “how this comes apart” alongside your “how this goes together” details.

- Use modular rooms and pods where churn is highestThink about where change is most likely – at workstations, casual or collaboration meeting areas, quiet zones, areas near entries and lifts. Consider a hybrid approach, built rooms for large, long-term needs; modular rooms/pods for flexible zones.

- Specify materials with genuine circular potentialPrioritise products with verified third-party EPDs, clear refurbishment or take-back and reuse options, and real, not theoretical, recycling pathways..

- Hand over a "circular dossier"Give the client something more useful than just a USB of PDFs: a simple register of what can be moved and reused as-is; what can be refurbished (e.g. panels, upholstery, hardware); where there are known take-back or recycling routes; and any modular room or pod systems identified with IDs that can be tracked over time.

This makes it far more likely that when someone stands on that floor in the future, they’ll see a palette of assets – not a demolition job.

From single projects to modular and circular portfolios.

The circular engineering strategy paints a picture of Australia in 2040 where:

Key targets for Australia's 2040 Circular Engineering Strategy, focusing on resource recovery, waste reduction, & sustainable industry. Credits: Engineers Australia, A National Strategy for a Circular Economy.

- High-value materials are circulating through multiple life cycles.

- Construction waste is dramatically reduced and better managed.

- Circular solutions are normal practice, not pilot projects.

For architects are designers, getting there isn't about one perfect "circular project". It's about building new habits:

- Developing repeatable room eco-systems based on modular systems that you can deploy across different clients and sectors.

- Building your own library of details, specs and briefs that explicitly support disassembly and reuse. Tracking what happens to your fit-outs over time and telling those stories - the rooms that moved instead of being demolished, the projects that saved on make-good because the system was designed for change.

That moment in 2008, with Braungart, was a blunt reminder that “sustainable” isn’t the finish line. Circular design is about something more ambitious: creating spaces, systems and products that are capable of multiple good lives, not one slightly less bad one.

Where I fit in: my work now sits right in this intersection, with Ecolution Design – a company founded in the Netherlands, world-leading in circular manufacturing of modular pods and meeting rooms.

Where I fit in: my work now sits right in this intersection, with Ecolution Design – a company founded in the Netherlands, world-leading in circular manufacturing of modular pods and meeting rooms.

Ecolution Design: From phone booths to large meeting spaces - each module designed for disassembly, refurbishment, & reuse. Credit: Ecolution Design (ecolutiondesign.eu)

If you’re exploring how to make your next fit-out, refurbishment or workplace concept genuinely circular – especially around enclosed spaces – I’m always up for a conversation, a workshop with your team, or a project-specific brainstorm.

Because if there's one thing that warm Sydney night with "the German Professor" taught me, it's this:

If you’re exploring how to make your next fit-out, refurbishment or workplace concept genuinely circular – especially around enclosed spaces – I’m always up for a conversation, a workshop with your team, or a project-specific brainstorm.

Because if there's one thing that warm Sydney night with "the German Professor" taught me, it's this:

We shouldn’t just remake how we make things...we should remake how we build things.